Salvador Dali Museum of Fine Arts Boston People in the Water

Knud Merrild was just near the merely avant-garde Los Angeles creative person whose work was caused by Louise and Walter Arensberg, the powerhouse collecting couple who moved from Manhattan to Los Angeles in 1921. In their jam-packed house in the Outpost foothills, a couple of blocks behind Sid Grauman's pseudo-Chinese extravaganza of a movie house on Hollywood Boulevard, a few small examples of Merrild's piece of work would somewhen be found.

Merrild (1894-1954) was an enigmatic creative person who is hardly a household proper noun today. Withal, some of his small pictures were tucked in amongst the staggering array of not-quite-yet globally acclaimed masterpieces by the likes of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Piet Mondrian, Constantin Brancusi, Fernand Léger, Salvador Dalí, Giorgio de Chirico and scores more.

Maybe nigh notable amid them was Dada founder Marcel Duchamp, the Arensbergs' favorite.

Merrild was a Danish-built-in expat. He had arrived in town a few years later on the Arensbergs did and, similar anyone with an interest in advanced art, gravitated to their home.

A small Surrealist abstraction by L.A. artist Knud Merrild is tucked below a Paul Klee painting and next to a large Fernand Léger canvas in the corner of the Arensbergs' dining room.

(Getty Publications)

His layered Cubist and Surrealist abstractions no dubiousness appealed to two of America'south near astute — and daring — collectors of Modern European art. (His friendship with the racy author D.H. Lawrence no incertitude helped.) Merrild would continue to develop an experimental technique that he chosen "flux painting," an oils-and-water method that allowed fluid colors to ooze, spread and seek their own marbleized shapes.

Merrild tipped and turned the small works earlier the fluid colors dried, but the mixed paint likewise moved with independent, chemically induced alertness. Beginning in 1942 and predating by a few years the radical baste paintings of Janet Sobel and Jackson Pollock, the flux compositions owe much to the mysterious vagaries of chance.

I've long wondered what might have inspired such a radically inventive arroyo to painting. Now in that location'southward a robust clue: A terrific new book from Getty Publications displays the nearly 1,000 works in the Arensbergs' collection in a fashion we've never seen before: room by room, wall by wall, tabletop past tabletop.

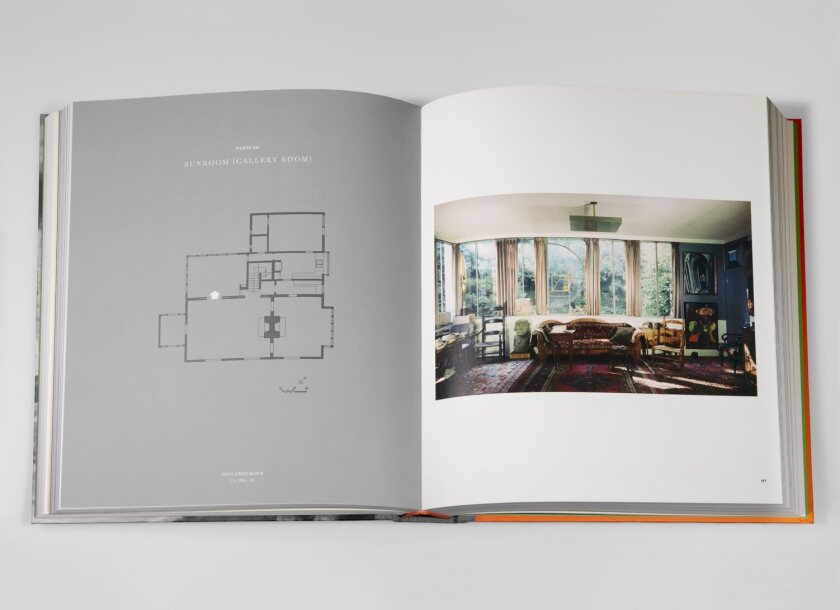

In the Arensbergs' Neutra-designed sunroom, a Duchamp relief on glass is installed in forepart of a window, correct.

(Karl Bissinger)

1 revelation is that, surely thanks to knowing the Arensbergs, Merrild was captivated past the ambiguous power of gamble.

At one time or another, the Arensbergs owned the lion's share of everything Duchamp made. (Multiple versions of his infamous "Nude Descending a Staircase" were in the house.) Engaging the mysterious properties of chance was a driving forcefulness in Duchamp'southward aesthetic. Merrild's puzzling, chance-driven work fit right into the collectors' phenomenal trove of European avant-garde paintings and sculptures.

A 2d, as surprising revelation is the degree to which pre-Hispanic art is central to the story.

A 1912 Picasso Cubist still life hangs adjacent to a 1913-14 Matisse portrait in the Arensbergs' living room.

(Charles Sheeler/Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

In L.A., the Arensbergs went total-throttle into collecting carved stone sculptures and painted ceramics fabricated in ancient United mexican states and Fundamental America. Sometimes, they would add a relevant Modernistic painting, such as Diego Rivera's "The Flowered Canoe."

That 1931 canvas, which held a prominent position in the home's central stairwell, shows more than half a dozen men and women on a Sunday outing in a pleasure boat on one of the famous canals in Mexico City'southward Xochimilco neighborhood. Figures fuse Cézanne-style abstraction with forms derived from sturdy Aztec sculpture.

(Fred R. Dapprich)

(Floyd Faxon)

If enigma and mystery were fuel for Dada and Surrealist art, including Merrild's flux paintings, what could exist more enigmatic and mysterious than ancient Aztec, Maya, Toltec and other pre-Hispanic fine art, which fine art historians were just beginning to intensely report and interpret? Walter Arensberg was specially drawn to unraveling historic puzzles. His other passion, aside from Modern art, was researching the writings of Francis Bacon, 17th century British "father of empiricism," including speculation on his authorship of Shakespeare's plays.

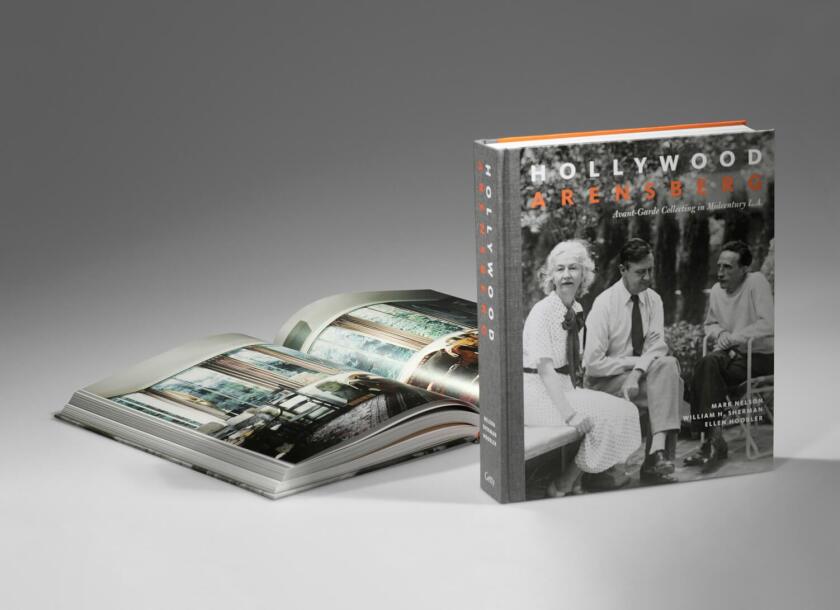

"Hollywood Arensberg: Avant-garde Collecting in Midcentury Fifty.A.," set to be released Oct. 22, is 432 pages of fascinating reconstruction of the collectors' house. Walter was heir to a Pittsburgh company involved with iron smelting, and Louise was a German language-built-in textile heiress whose wealth funded their collecting enterprise. Their 1920 Mediterranean Revival firm, with a sunroom added later by Modernist Richard Neutra, was designed by William Lee Woollett, architect of Broadway's Million Dollar Theater downtown.

A reader travels room past room through the two-story abode. Side trips explore the gardens. At that place, monumental pre-Hispanic sculptures held sway.

Los Angeles fine art lore is filled with Arensberg stories — virtually their astonishing drove; their close friendship with Duchamp; the life-altering visit to their domicile past a weird young kid from Eagle Rock named Walter Hopps, who would continue to become an internationally of import curator; their futile efforts to detect a permanent museum domicile for their astounding art in Los Angeles and a dozen other cities (the Philadelphia Museum of Art finally agreed); and more. But only a few photographs of the home's interior have been widely seen.

Those are now amplified immeasurably. Several dozen ballast the book.

Visitors to Philadelphia can happily see much of the collection. But the experience of categorized institutional system is wholly dissimilar from the freewheeling environment on Hillside Avenue. In a new foyer designed by architect Henry Palmer Sabin, for example, an arriving guest is immediately greeted by a smashing — and startling — display.

Constantin Brancusi's sculpture "Princess X" is surrounded by Aztec stone sculptures — and a dinosaur footprint — in the Arensbergs' lobby.

(Floyd Faxon)

A Brancusi curvation of rough-hewn oak frames a sleekly phallic Brancusi sculpture of a woman's head, "Princess X," in polished bronze, semi-erect atop a smooth limestone cube. (The artist once slyly described the controversial work every bit "Goethe's 'Eternal Feminine' reduced to its essence.") Numerous pre-Hispanic carved stone sculptures are also displayed, including big heads of a jaguar and a serpent and a big ballcourt ring, all Aztec.

Brancusi is enshrined inside a powerful array of not-Classical antiquities, setting aside European sculptural traditions from Greece and Rome. For emphasis, the elemental ensemble features one prehistoric anomaly — a stone slab embedded with a dinosaur footprint.

The footprint fossil turned out to exist fake. Notwithstanding, that's a house I'd like to see. The volume helps a reader do it.

(Getty Publications)

Walter and Louise Arensberg, pictured at left on the book's cover, were major collectors of Dada artist Marcel Duchamp, right.

(Beatrice Woods)

There are enlightening essays and enquiry notes by authors Marking Nelson, a book designer; cultural historian William H. Sherman, managing director of London's Warburg Institute; and Ellen Hoobler, a curator at Baltimore'due south Walters Art Museum. The thick tome is marvelously designed, the layout marked by coherent simplicity.

The scheme is a sort of scholar's version of a 3-D dwelling tour on a real estate website.

For each room, besides equally the grounds, a documentary photograph on the right faces a floorplan on the left. (Most photographs are black-and-white.) A small-scale pointer on the floorplan indicates the spot from which the picture show was taken, and the direction.

Turn the folio, and a numbered line drawing on the correct picks out every art object in the preceding photograph. A numbered list on the left page identifies the corresponding art in the line drawing opposite.

Some of the photographs zoom in. Others show the same room in different years. New art objects arrive, paintings move effectually, the installation changes.

People are rarely seen — except for occasional groups of soldiers visiting from a nearby hospital, or mayhap the Hollywood Canteen, belatedly in World War Two.

The Arensbergs lived in the house for almost xxx years. Art dealer Earl Stendahl, source of some of the Modern work and virtually all of the pre-Hispanic art (including knowingly looted items), moved in next door.

Louise Arensberg died in November 1953 at 74. Less than two months later, Walter, 75, followed her. Stendahl bought the property and opened a private gallery. An incomparable chapter in the history of great art collecting closed. Surely, this captivating volume will inspire new avenues of exploration.

Source: https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2020-10-01/hollywood-arensberg-book-art-collecting

0 Response to "Salvador Dali Museum of Fine Arts Boston People in the Water"

Post a Comment